Resurrection

Documents

Iconography of the Resurrection

The representations of the Resurrection are less numerous and widespread than other episodes in the life of Christ.

On the Resurrection the Gospel account is very meager.

There is a theme, not addressed by the canonical Gospels, except for an allusion in the 1st Letter of Peter ("And in spirit he went to proclaim salvation even to the spirits who were waiting in prison" 3,19), which is inspired by the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus and also spreads in the West through the Speculum Humanae Salvationis by Vincent of Beauvais and the Legenda Aurea by Jacopo da Varagine.

The liberation of the unbaptized righteous is associated with Christ's entry into Limbo.

According to the most common scheme Christ, armed with the cross of resurrection, tramples the gates of the Underworld - sometimes arranged in a cross - whose hinges strike Satan or stick the tip of the cross into the throat of the Leviathan; overcoming these obstacles he grabs the arm of Adam, the first to be freed, behind which Eve is often recognizable, kneeling; and then Abel also appears,Abraham, David, Solomon, Samson, John the Baptist, the good thief and a host of other righteous awaiting salvation. One of the first examples of the Descent into Limbo in Byzantine art is in a column of the ciborium of San Marco in Venice, but it is also found in the mosaics of the 11th and 12th centuries. in S.Marco, in Torcello and in Monreale. The first depictions in Western art, however, are the frescoes of Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome (8th century) and in the underground church of San Clemente (9th century). Then there are the Descent into Limbo on the back of Duccio's Majesty and the paintings by Bronzino and Tintoretto, but except in rare cases this iconographic theme disappears from the repertoire of Christian art from the seventeenth century.

According to the most common scheme Christ, armed with the cross of resurrection, tramples the gates of the Underworld - sometimes arranged in a cross - whose hinges strike Satan or stick the tip of the cross into the throat of the Leviathan; overcoming these obstacles he grabs the arm of Adam, the first to be freed, behind which Eve is often recognizable, kneeling; and then Abel also appears,Abraham, David, Solomon, Samson, John the Baptist, the good thief and a host of other righteous awaiting salvation. One of the first examples of the Descent into Limbo in Byzantine art is in a column of the ciborium of San Marco in Venice, but it is also found in the mosaics of the 11th and 12th centuries. in S.Marco, in Torcello and in Monreale. The first depictions in Western art, however, are the frescoes of Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome (8th century) and in the underground church of San Clemente (9th century). Then there are the Descent into Limbo on the back of Duccio's Majesty and the paintings by Bronzino and Tintoretto, but except in rare cases this iconographic theme disappears from the repertoire of Christian art from the seventeenth century.FOR ICONOGRAPHY, AT EASTER,

THE MESSAGE TO BE TRANSMITTED IS ALWAYS:

RESURREXIT DOMINUS VERE!

(The Lord is truly risen!).

At the origins of the Church, however, the Resurrection of Christ is represented by the image of the Mirophoras (Bearers of the ointments) who on Easter morning go to the tomb with the aromas and find it empty; their sadness turns into the joy of having been the first witnesses and heralds of the Risen One.

The Gospels do not agree on the number of women who at the tomb saw "an angel of the Lord, who came down from heaven" (Mt 28,2): they are two for Matthew, three for Mark and Luke and only the Magdalene for John. The apparition of the angel, whose "appearance was like lightning and his dress as white as snow" (Mt 28,3), is a real Theophany that scares women and makes soldiers flee. This theme, present in early Christian art, already appears in the murals of the baptistery of Dura Europos, in which the tomb of Christ is represented as a large stone sarcophagus, similar to those used in the region. Very particular is the tomb in the shape of a small sanctuary, depicted in the Munich ivory (5th century), where the women are placed next to a kind of chapel, probably a simplified reproduction of the one built in the 4th century on the site of the Holy Sepulcher, with two sleeping guardians.  In the upper register the ivory includes the curious detail of Peter, James and John falling asleep on the slope of the hill from which Christ ascends with the help of the Father, whose hand emerges from heaven.The meaning seems to be that the glory revealed to the three apostles in the Transfiguration is definitively realized only in the Resurrection-Ascension of the Savior.

In the upper register the ivory includes the curious detail of Peter, James and John falling asleep on the slope of the hill from which Christ ascends with the help of the Father, whose hand emerges from heaven.The meaning seems to be that the glory revealed to the three apostles in the Transfiguration is definitively realized only in the Resurrection-Ascension of the Savior.

In the upper register the ivory includes the curious detail of Peter, James and John falling asleep on the slope of the hill from which Christ ascends with the help of the Father, whose hand emerges from heaven.The meaning seems to be that the glory revealed to the three apostles in the Transfiguration is definitively realized only in the Resurrection-Ascension of the Savior.

In the upper register the ivory includes the curious detail of Peter, James and John falling asleep on the slope of the hill from which Christ ascends with the help of the Father, whose hand emerges from heaven.The meaning seems to be that the glory revealed to the three apostles in the Transfiguration is definitively realized only in the Resurrection-Ascension of the Savior.In Duccio's Majesty we see the pious women, among them the Magdalene recognizable by the red mantle, who each carry a jar of ointments and withdraw in fear at the sight of the angel, dressed in white, holding the Ostiari's wand in her hand, he qualifies him as an assistant to divine ceremonies, and which points them to Galilee, where the risen Christ awaits his disciples. In the fresco by Fra Angelico in Florence, however, the figure of Jesus holding the banner and the palm branch, a symbol of martyrdom and glory, is associated with the scene of Mirofore. Here the women are four, the three Marys and the Magdalene, who remains far from the group, while the angel, always dressed in white, is seated on the sarcophagus and with hand gestures explains what has happened, showing the empty tomb and pointing towards the top, where the disciples will be able to see Jesus again. Only Luke mentions two angels seated on the sepulcher and in a 17th century canvas the shroud, held up by the angels with the fingertips, blends with the traditional iconography of Veronica's veil.

In some Romanesque churches we find, as a prelude to the visit to the tomb, the scene of the Mirophores who buy the aromas from perfume sellers; is a theme inspired by the liturgical drama and in a bas-relief of the facade of the church of Saint-Gilles-du Gard the sequence is represented in a realistic, even anecdotal way: the women wait in front of a stall behind which two merchants are seated, one of the which weighs the perfumes.In the Gospel of John (20: 1-8) the account of Jesus' encounter with women is expanded with the description of Mary Magdalene's visit to the tomb, the appearance of the angels and the encounter with Christ believed to be the gardener, who he calls her and she, recognizing him, tries to embrace him; hence the theme of 'Noli me tangere'.

hence the theme of 'Noli me tangere'.

hence the theme of 'Noli me tangere'.

hence the theme of 'Noli me tangere'.In Italian art this iconography developed especially in the fourteenth century and if then the angels and the empty sepulcher still appear, perhaps even with the sleeping guards, as in Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel, from the 15th century the scene tends to be restricted to the two protagonists and takes place in the garden, which then becomes a pretext for the description of a botanical microcosm. In the famous fresco by Fra Angelico, however, the garden is a 'hortus conclusus', a reference to the rediscovered Eden, where Christ is the new Adam; in the background the evergreen trees, symbol of eternal life, are a palm, a cypress, an olive tree and a pine, that is the same woods with which, according to tradition, the cross was made and that Angelico depicts in many of his works . Christ, with the white robe of the risen one, but with the hoe on his shoulder, seems 'light', almost touching the lawn, which in turn is sprinkled with symbolic flowers, but, beyond the naturalistic species, they are white flowers and reds that recall the Incarnation and the Passion, both of which took place in spring. Christ with the hoe and the straw hat is represented as early as the 11th century, but from the 13th century his figure is also enriched by the mantle and the Crusader staff of the Resurrection, as in Duccio's Majesty.

in the background the evergreen trees, symbol of eternal life, are a palm, a cypress, an olive tree and a pine, that is the same woods with which, according to tradition, the cross was made and that Angelico depicts in many of his works . Christ, with the white robe of the risen one, but with the hoe on his shoulder, seems 'light', almost touching the lawn, which in turn is sprinkled with symbolic flowers, but, beyond the naturalistic species, they are white flowers and reds that recall the Incarnation and the Passion, both of which took place in spring. Christ with the hoe and the straw hat is represented as early as the 11th century, but from the 13th century his figure is also enriched by the mantle and the Crusader staff of the Resurrection, as in Duccio's Majesty.

in the background the evergreen trees, symbol of eternal life, are a palm, a cypress, an olive tree and a pine, that is the same woods with which, according to tradition, the cross was made and that Angelico depicts in many of his works . Christ, with the white robe of the risen one, but with the hoe on his shoulder, seems 'light', almost touching the lawn, which in turn is sprinkled with symbolic flowers, but, beyond the naturalistic species, they are white flowers and reds that recall the Incarnation and the Passion, both of which took place in spring. Christ with the hoe and the straw hat is represented as early as the 11th century, but from the 13th century his figure is also enriched by the mantle and the Crusader staff of the Resurrection, as in Duccio's Majesty.

in the background the evergreen trees, symbol of eternal life, are a palm, a cypress, an olive tree and a pine, that is the same woods with which, according to tradition, the cross was made and that Angelico depicts in many of his works . Christ, with the white robe of the risen one, but with the hoe on his shoulder, seems 'light', almost touching the lawn, which in turn is sprinkled with symbolic flowers, but, beyond the naturalistic species, they are white flowers and reds that recall the Incarnation and the Passion, both of which took place in spring. Christ with the hoe and the straw hat is represented as early as the 11th century, but from the 13th century his figure is also enriched by the mantle and the Crusader staff of the Resurrection, as in Duccio's Majesty.After 1300 the theme of the Resurrection begins to be depicted in its own right: Christ rises from a stone sarcophagus and holds a banner with the cross in his hand, while the soldiers next to him are immersed in sleep: once again it is a matter of an image taken from the religious theater.

The Resurrection, in fact, was the main subject of these liturgical performances, but the evangelical fact was expanded with other stories and the details derived from this type of representation can be found on the portals and capitals of the churches of Europe.

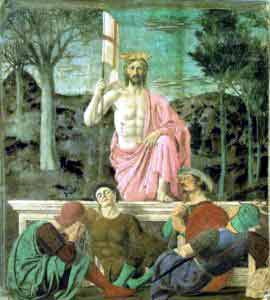

Christ is represented while standing in the tomb or resting a foot on the edge of the tomb, as in the Resurrection by Piero della Francesca in Sansepolcro and by Mantegna in the predella of the altarpiece of San Zeno, or standing on the sarcophagus as if it were a pedestal in a lunette by Luca della Robbia.

The Resurrection of Piero, in particular, should be read in the light of the liturgy and the sacred dramaturgy from which it emanates, since the fresco reproduces the scheme of a fourteenth-century altarpiece, where the parallelism between the depicted sarcophagus and the royal altar is full of meaning. In fact, medieval liturgists saw a figure of the sepulchrum Christi in the altar. This Christ of the Resurrection enlivens the entire universe: the trees and the earth on his right are still naked and wintery, while on the other side they are green, springtime, so that the normal reading of the image, from left to right, forces us to see the annual rebirth of nature in relation to the Savior's return to life.

An important iconographic variant, which later became the most widespread, shows the upward movement of the glorious Christ hovering over the open tomb; this iconography has many similarities with that of the Transfiguration and the Ascension, and appears for the first time in the fourteenth century. and for the entire following century it will be exclusively Italian. Among the most famous resurrections are those of Titian, Tintoretto, Tiepolo and in these cases the angels overturn the stone of the tomb from which the Risen Christ emerges surrounded by light and carries a cross or banner as a banner of victory, but it can also show the wounds of crucifixion, such as the smiling Christ from the luminous globe by Matthias Gruenewald. The difficulty of representing the event in its most crucial moment is clearly justified by the Gospel texts, in which the before and after are told, but not the fact itself, the very event of the Resurrection. The Resurrection comes imagined and represented as a luminous explosion, whose source is Christ himself, the sun of justice and victory, who rises over the darkness of death and wears a robe whose colors immediately refer to the Transfiguration; the representation of glory is completed by the banner of victory, consisting of a cross or a staff surmounted by a weather vane, sometimes with a cross This is the iconographic image that has become more widespread in recent centuries: even contemporary sacred art has dealt with this theme several times, and the most famous example is the Resurrection (1972-77) by Pericle Fazzini, created at the invitation of Paul VI for the Sala Nervi in

The difficulty of representing the event in its most crucial moment is clearly justified by the Gospel texts, in which the before and after are told, but not the fact itself, the very event of the Resurrection. The Resurrection comes imagined and represented as a luminous explosion, whose source is Christ himself, the sun of justice and victory, who rises over the darkness of death and wears a robe whose colors immediately refer to the Transfiguration; the representation of glory is completed by the banner of victory, consisting of a cross or a staff surmounted by a weather vane, sometimes with a cross This is the iconographic image that has become more widespread in recent centuries: even contemporary sacred art has dealt with this theme several times, and the most famous example is the Resurrection (1972-77) by Pericle Fazzini, created at the invitation of Paul VI for the Sala Nervi in

These triumphal images do not fit the spirit of the Protestant reform, for which Rembrandt, for example, interprets the scene making it similar to the Resurrection of Lazarus: an angel lifts the stone and Christ comes out of the tomb still wrapped in bandages.

The difficulty of representing the event in its most crucial moment is clearly justified by the Gospel texts, in which the before and after are told, but not the fact itself, the very event of the Resurrection. The Resurrection comes imagined and represented as a luminous explosion, whose source is Christ himself, the sun of justice and victory, who rises over the darkness of death and wears a robe whose colors immediately refer to the Transfiguration; the representation of glory is completed by the banner of victory, consisting of a cross or a staff surmounted by a weather vane, sometimes with a cross This is the iconographic image that has become more widespread in recent centuries: even contemporary sacred art has dealt with this theme several times, and the most famous example is the Resurrection (1972-77) by Pericle Fazzini, created at the invitation of Paul VI for the Sala Nervi in

The difficulty of representing the event in its most crucial moment is clearly justified by the Gospel texts, in which the before and after are told, but not the fact itself, the very event of the Resurrection. The Resurrection comes imagined and represented as a luminous explosion, whose source is Christ himself, the sun of justice and victory, who rises over the darkness of death and wears a robe whose colors immediately refer to the Transfiguration; the representation of glory is completed by the banner of victory, consisting of a cross or a staff surmounted by a weather vane, sometimes with a cross This is the iconographic image that has become more widespread in recent centuries: even contemporary sacred art has dealt with this theme several times, and the most famous example is the Resurrection (1972-77) by Pericle Fazzini, created at the invitation of Paul VI for the Sala Nervi inVatican, a work in which the vitality of the Risen One in the post-conciliar Church pulsates, sharing in the joys and hopes, sufferings and anxieties of modern man. Fazzini, in fact, conceives the Resurrection in relation not only to the physical agony of the cross but also to the moral agony of the Garden of Gethsemane and writes that he created Christ "as if he would rise again from the outbreak of this great olive grove". The sculpture, a large bronze 20 m long, has the appearance of an explosion of matter, of a primordial chaos in which it is impossible to distinguish and divide the multitude of naturalistic elements that intertwine and merge, rocks, branches, twigs. , roots, from which a central human figure emerges. The composition tends upwards, a metaphor for a search for the divine from which man cannot escape. Vatican, a work in which the vitality of the Risen One, present in the post-conciliar Church, participates in the joys and hopes, in the sufferings and in the anxieties of modern man. Fazzini, in fact, conceives the Resurrection in relation not only to the physical agony of the cross but also to the moral agony of the Garden of Gethsemane and writes that he created Christ "as if he would rise again from the outbreak of this great olive grove". The sculpture, a large bronze 20 m long, has the appearance of an explosion of matter, of a primordial chaos in which it is impossible to distinguish and divide the multitude of naturalistic elements that intertwine and merge, rocks, branches, twigs. , roots, from which a central human figure emerges. The composition tends upwards, a metaphor for a search for the divine from which man cannot escape.Very interesting for their ability to combine contemporaneity and tradition, are the images that illustrate the Resurrection present in the new CEI Lectionaries: it is a pity that they are little used and there is still a lot of distrust towards the artistic expressions of our century!

Fazzini, in fact, conceives the Resurrection in relation not only to the physical agony of the cross but also to the moral agony of the Garden of Gethsemane and writes that he created Christ "as if he would rise again from the outbreak of this great olive grove". The sculpture, a large bronze 20 m long, has the appearance of an explosion of matter, of a primordial chaos in which it is impossible to distinguish and divide the multitude of naturalistic elements that intertwine and merge, rocks, branches, twigs. , roots, from which a central human figure emerges. The composition tends upwards, a metaphor for a search for the divine from which man cannot escape.Very interesting for their ability to combine contemporaneity and tradition, are the images that illustrate the Resurrection present in the new CEI Lectionaries: it is a pity that they are little used and there is still a lot of distrust towards the artistic expressions of our century!

Fazzini, in fact, conceives the Resurrection in relation not only to the physical agony of the cross but also to the moral agony of the Garden of Gethsemane and writes that he created Christ "as if he would rise again from the outbreak of this great olive grove". The sculpture, a large bronze 20 m long, has the appearance of an explosion of matter, of a primordial chaos in which it is impossible to distinguish and divide the multitude of naturalistic elements that intertwine and merge, rocks, branches, twigs. , roots, from which a central human figure emerges. The composition tends upwards, a metaphor for a search for the divine from which man cannot escape.Very interesting for their ability to combine contemporaneity and tradition, are the images that illustrate the Resurrection present in the new CEI Lectionaries: it is a pity that they are little used and there is still a lot of distrust towards the artistic expressions of our century!

Fazzini, in fact, conceives the Resurrection in relation not only to the physical agony of the cross but also to the moral agony of the Garden of Gethsemane and writes that he created Christ "as if he would rise again from the outbreak of this great olive grove". The sculpture, a large bronze 20 m long, has the appearance of an explosion of matter, of a primordial chaos in which it is impossible to distinguish and divide the multitude of naturalistic elements that intertwine and merge, rocks, branches, twigs. , roots, from which a central human figure emerges. The composition tends upwards, a metaphor for a search for the divine from which man cannot escape.Very interesting for their ability to combine contemporaneity and tradition, are the images that illustrate the Resurrection present in the new CEI Lectionaries: it is a pity that they are little used and there is still a lot of distrust towards the artistic expressions of our century!It is certain that there is art and art, but it is always true that Christus vere resurrexit!